London was wiped out shortly after the USSR perfected their H-Bomb. It could so easily have happened in real life, but thankfully it was only to be on British Civil Defence plans that our capital city was erased and replaced by “Area 5a”.

It is extraordinary how quickly the ubiquity of Civil Defence planning has been forgotten, yet it contributed a huge amount to our contemporary way of life, and an explosion of commuter suburbs oriented towards cold war aeronautics and economics. A volunteer Civil Defence Corps, which never quite got to full strength, prepared, drilled and enjoyed pot-luck dinners and dinner dances. It was manned by joiners-in, optimists, patriots, and the kind of aggrandised social secretaries who George Orwell feared might pervert the course of English Socialism towards Totalitarianism. The CDC is a much better fit for 1984 than a cut and paste job between the USSR and UK. But Dystopia isn’t the only treatment World War Three gets on film and in literature. Surrealistic Satire is particularly suited to depicting Mutually Assured Destruction.

This song’s airplay was restricted for fear it would undermine morale. I’m not sure if it is Satire or just plain silly, but Satire has attracted legal action for millennia. Litigation is its litmus test. It’s silliness is altogether different to the absurdity of officially approved images and advice offered to citizens by Civil Defence; Civil because the Home Front is the new Front Line in nuclear conflict. The Family fall-in to prepare for the fallout.

One thing you should take away from this presentation is that it takes 16” of books to protect you from the fallout. There is no point cowering behind a Kindle. If you find Finnegans Wake hard going, be thankful that the gamma rays will too. Yet how many families have this many books? Perhaps a Civil Servant might, or a Professor. The central thing we should take away from this slideshow presentation is that official Civil Defence advice for surviving M.A.D. was itself insane. Insane in a cold-blooded clear-headed calculated kind of way. But what was the real agenda? Look at this man:

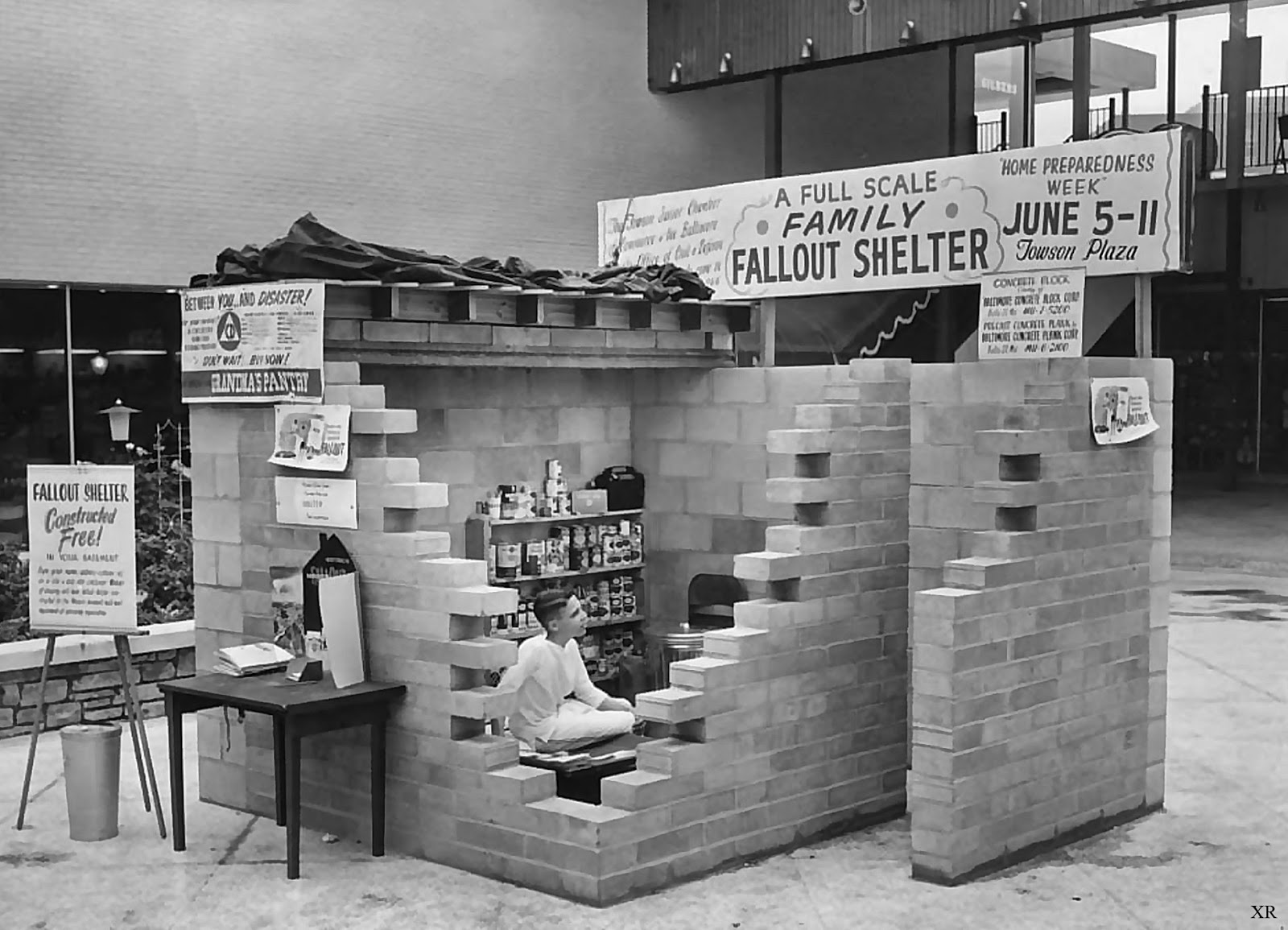

He doesn’t really think you stand a chance, but he has a job to do. A story to tell. In the USA, approved plans were available from Civil Defence, in the UK the unhinged advice was that a door turned on it’s side would do the job, yet you too could have built your own fallout shelter in the basement or bought one from a contractor. Or what better way to return to the Dark Ages than in your very own barrow.

You could try role-playing as King Arthur, returning to rescue Albion, to keep up morale.

Depicting this as an Ideal Home Exhibition for the nuclear family enabled the authorities to create the fiction that everything will be alright. That the institutions of government, family and law and order would survive. Everything is under control.

But it wasn’t. Our technical ability had outstripped our humanity. Governments were being dragged towards disastrous conflict by their nuclear weapons like two men taking too many pitbulls for a walk.

These slideshows are obsessed with morale. The family enjoys a game. Later, how about a nice game of chess? Plan a varied diet for interest: pasta, pulses, dried fruit, or a stray dog, perhaps? While the male constructs a shelter, the housewife undertakes stockpiling with the children. The fixed benign grins in these slides are like the ones you find in safety advice leaflets you get on a plane, yet here we have Olympic level denial. And endless stacking. Keeping organised, prepared, civilised.

It’s like a miserable family holiday. With parents who are making the best of it, chirpy and chipper, and clinging on desperately to institutions that have become null and void.

The Bed-Sitting Room, a play by Spike Milligan and John Antrobus adapted for film by Richard Lester, exploits this disparity between reality and defeated institutions brilliantly. Their characters feed off those institutions like rations stockpiled in their memories. Memories of London – the City only exists in their heads.

The authorities are now two madmen in a makeshift hot-air balloon (Peter Cook and Dudley Moore), yet the survivors constantly submit to them and the bureaucratic language that is mangled by their jobsworth tongues. The survivors often ask where in reality they are.

If this is Regent’s Park, then to the South..

I must get to Belgravia..

Don’t you know your London?

Why, this is Paddington!

In The Human Condition, Hannah Arendt argued that the Patriarch that once ruled the household in Greco-Roman society was replaced in the modern nation state by Bureaucracy. She describes a mental picture of a table that has vanished yet leaves everyone seated in the same position.

So we see ancient household concerns, like wealth and health become elevated to a kind of national housekeeping, the Economy and Healthcare system. Yet the difference is hard to spot because individuals occupy so many of the same roles as before and labour to satisfy similar needs. At one level Civil Defence was just this kind of interference, one of the many bureaucratic structures that filled the void where the patriarch once stood. But what happens if the unimaginable happens and Bureaucracy itself is destroyed, leaving a few atomised families to encircle a power-vacuum?

In the Bed-Sitting Room this is precisely the kind of shift that takes place. The authorities have created the conditions for their own destruction and the family they have failed to protect fail to grasp that Britain is over. American disaster movies often revolve around a family unit (or surrogate) pitted against distant odds. The Bed-Sitting Room is far more British in that it is about institutions. “I am the BBC,” intones the telly man.

The characters are Nurses, Doctors, Soldiers, Police, a Priest, all covering themselves with the signs of institutions that have been destroyed, “because we’re British?” One could even say that a film depicting a family buffeted around a political vacuum, shambling around a china clay pit obsessing over the past is a perfect parable for Britain today. It is what happens when the social structure described by Foucault (or Hobbes) wherein people practice mutual oppression through a sovereign, through uniforms and rituals, loses its centre, its elastic tension, and it slaps them in the face with official clobber. Their sovereign investment is returned with insufficient postage paid. Either they get dressed or they admit that it’s all over. It is all over. The charade has become an obvious charade.

But why is Satire so appropriate for imagining nuclear war? Or World War One for that matter? There are several references to it in The Bed-Sitting Room. Oh What A Lovely War is a very similar film in its surreal imagery and biting satire.

The connection is the unthinkable destruction. After World War Three the past, present and future would all have been destroyed. Satire works in the opposite direction to the Civil Defence slideshow. Satire’s hysterical absurdity makes the viewer more sane, not less. It removes delusion by revealing its contradictions. The slideshow, however, invites you to share a collective delusion and ingrain it in yourself through pointless activity.

This has always been Satire’s agenda. Indeed, the purpose of all Greek plays was to protect society from corruption. A tragedy like Antigone was performed by and for the politicians of the city state to remind them that tyrants like Creon will always lead them to disaster. The Old Comedy of Aristophanes, satires such as The Birds, had the same job. But they did it through shaming those who were already corrupt.

Every theory needs a control sample, so let’s take a straightforward thriller like WarGames from 1983. Ferris Bueller has an even more disastrous day off when he hacks into the Pentagon and plays Thermonuclear War. The computer locks out the authorities and it looks like World War Three is unavoidable.

As we know, the US Govt. takes a very tolerant view of hackers, so they allow him to give it one more good old college try.

He makes the computer play itself at noughts and crosses, which always ends in a stalemate. The computer cross references this with thermonuclear war and realises that it can only win by not playing. This is the intended message of the film. However, satire is lurking in the wings and subverts the final scene with this:

“How about a nice game of chess.” Chess? The game based on grinding seasonal medieval warfare? Chess is the home game of Henry V! This film ends up subverting itself and asking, what do you do when you can’t play nuclear war? Play proxy war! *The military history of the post-war years explained in a single unintended joke about chess*. A joke that says you can’t ‘not play’ nuclear war – you can’t turn the clock back. The truth is that nuclear weapons are not a mistake. They are a perfect expression of what we are like as a species. They are what you get when you multiply our accelerating technical ability with our inhumanity to man. This is what happened in World War One. The only way to get rid of these weapons for good is for all of us to become the kind of creature that can make them, but chooses not to. But I fear this work is overdue and nuclear weapons will not be abolished. Rather they will be superseded by weaponised Fusion Power. Our chance to not create this is fading, and another technology that should spell free energy for all will spread ubiquitous fear, just in case “the others make it first”. Can we ever unlearn this logical fault?

Satire is one of the arts that allows us to imagine a way out. The Bed-Sitting Room invites us to become more humane by laughing at our self-destructive self-delusion. But this makes it even more worrying that our politicians are so uncultured and unliterate.